The Dr. Manhattan Dilemma

The tragic story of a man who became The Clockwork god.

Reading Time estimated: 14 minutesImagine for a moment that you could shed your human mortality. You would be immortal, even possess godlike powers over space and time. What would you do? It's a compelling question that has fascinated scientists and philosophers alike…and probably you too, since you clicked on this essay.

Let’s dive in:

CHAPTER 1: Who is Jon Osterman?

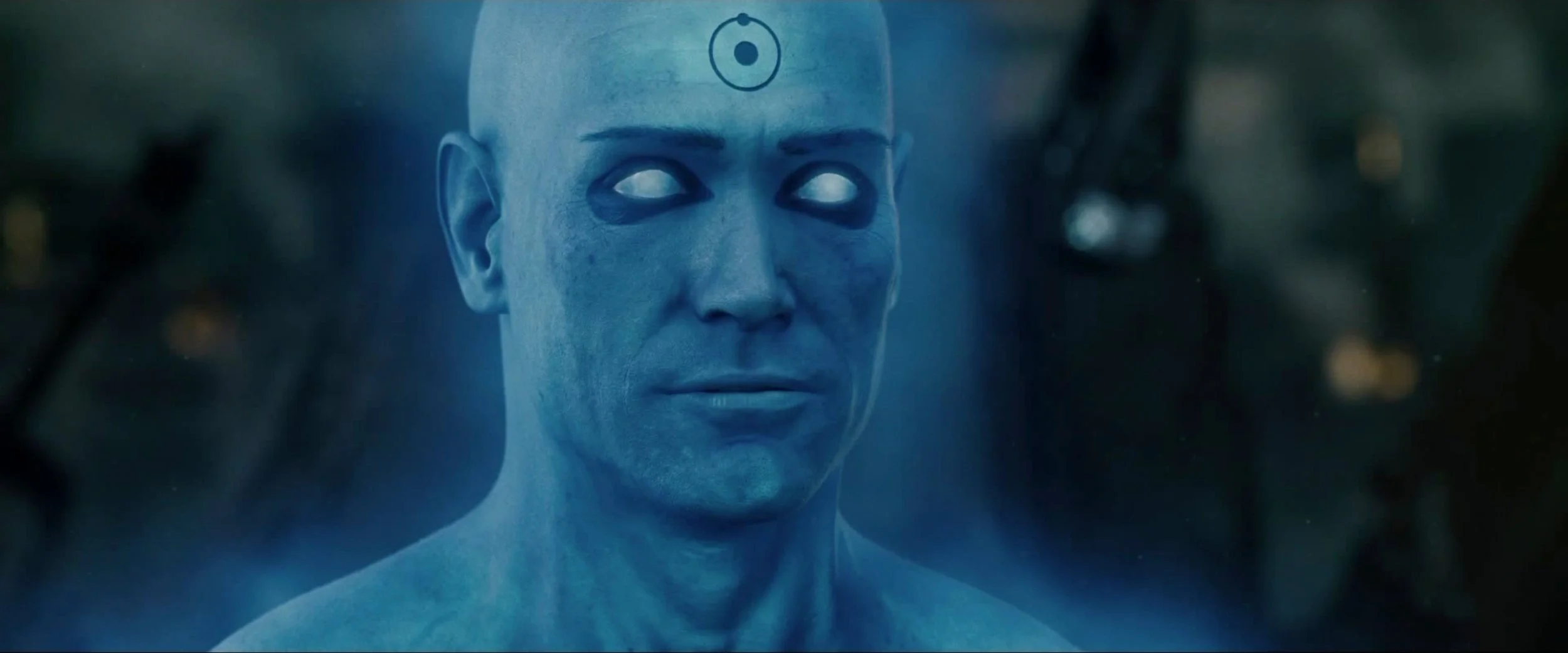

Jon Osterman was a brilliant nuclear physicist whose life changed forever after a tragic accident at the Gila Flats Test Base.

Raised in Brooklyn, Jon’s path was shaped by the atomic age. After the bombing of Hiroshima, his father gave up clockmaking and urged Jon to pursue nuclear science. Jon attended Princeton University from 1948 to 1958, where he studied nuclear physics. During his time there, he witnessed a lecture by Albert Einstein and formed lasting friendships with fellow students. His PhD focused on the neutrino theory of light involving C-waves. When his dissertation was accepted in May 1958, he earned a Doctorate of Philosophy in Nuclear Physics. This achievement led to a research position at the Gila Flats Test Base in New Mexico. His good friend Wally Weaver introduced him to his later girlfriend Janey Slater.

While retrieving a watch he had promised to repair for Janey, Jon became trapped inside a test chamber during a radioactive particle experiment. The resulting exposure disintegrated his body. Jon Osterman ceased to exist. In his place emerged someone, or something… else. The world would come to know him as Dr. Manhattan.

Dr. Manhattan is one of the most powerful beings in pop culture and a central character in Watchmen. Watchmen is a graphic novel published in 1986/87 by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, originally released as a twelve-part series by DC Comics. Dr. Manhattan is nearly indestructible, omnipresent, and godlike.

» His abilities include:

Immortality: Dr. Manhattan is immune to physical harm, aging, and death.

Teleportation: He can instantly move to any location on Earth or in other dimensions.

Energy and matter manipulation: He can release energy, manipulate matter, and even alter reality.

Precognition and telepathy: He can see the future and read minds.

Superhuman strength: He is physically unbreakable and extremely strong.

Transformation and regeneration: He can reshape his body and heal himself or others.

His origin story starts like many classic superhero tales. Whether bitten by a spider, enhanced by a serum, or chosen by an alien force—Jon Osterman didn’t choose his powers. The watch he tried to save would come to symbolize much more—both his tragic fate and the deeper themes of Watchmen. Soon, time itself would cease to hold meaning for him.

CHAPTER 2: How Immortality Affects the Human Spirit

The finiteness of life and the inevitability of death, is a double-edged sword. While some fear death, others find that it’s what gives life meaning. So, what does science have to say about it?

Terror Management Theory (TMT)

This psychological theory proposes that awareness of one’s own mortality ("mortality salience") triggers existential terror, which people counter by embracing cultural worldviews, religions, or moral systems. These frameworks give them a sense of meaning, permanence, and order. Studies show:

When reminded of death, people tend to apply stricter moral judgments.

They show increased loyalty to their in-group and hostility toward out-groups.

Some become more altruistic, others more conservative—depending on worldview.

Neuroscience & Psychology

Thinking about mortality activates the emotional centers of the brain, especially the amygdala (fear) and the prefrontal cortex (reflection, ethics). Regular confrontation with death e.g. through mindfulness or meditation can:

Increase focus on interpersonal relationships.

Strengthen appreciation of the present moment.

Shift priorities toward meaning and the common good.

Simulated Immortality

Humans aren’t biologically immortal, but experiments examine how people behave when death seems far away or improbable:

Reduced sense of responsibility: People who believe they have “endless time” (e.g. many young people) tend to procrastinate, take more risks, and live with less purpose.

TMT revisited: If mortality awareness strengthens morality, its absence might lead to moral detachment. Some studies show that people who see themselves as "beyond death" (e.g. through religious beliefs in immortality) may show less empathy and responsibility—especially toward outsiders.

Technological Immortality (Transhumanism)

In debates about digital consciousness uploading or biological extension, researchers and ethicists point out:

Without finitude, time loses value, decisions lose weight, and relationships lose depth.

An "eternal now" may lead to existential boredom (see: hedonic treadmill).

Humans may become morally stunted—because aging, suffering, and death are crucial sources of empathy and responsibility.

Let’s shift to a philosophical view:

Existentialism (e.g. Sartre, Heidegger, Camus)

Death is not a flaw but an essential part of being.

Heidegger emphasizes "being-toward-death": Only by embracing our mortality do we become truly authentic.

Camus introduces the “absurd hero”: Although life may be objectively meaningless, we can still create subjective meaning especially in the face of death.

Ethical Implications (Kant, Schopenhauer)

Kant: Awareness of death supports a sense of duty, living life according to moral law.

Schopenhauer: Compassion (sharing in the suffering of fellow mortals) is the foundation of morality.

Buddhist Philosophy

Reflection on impermanence (Anicca) is a central practice for overcoming ego and attachment. Mortality is not feared but embraced as a teacher.

Bernard Williams – “The Makropulos Case” (1973) In this famous essay, Williams argues:

Immortal life leads inevitably to boredom, apathy, and loss of identity.

Mortality is necessary for purpose, desire, and meaning—without death, there is no urgency.

Humans stagnate psychologically once all desires have been fulfilled.

Nietzsche – Eternal Recurrence

Nietzsche flips the concept: rather than praising eternal life, he challenges us to imagine reliving our lives endlessly. Only a meaningful life is worth repeating—demanding radical self-responsibility and affirmation.

Camus & Absurdism

Camus would argue that death gives life dignity. A world without death would lack drama, tragedy and ultimately, meaning.

Immortality sounds appealing, but often turns out to be psychologically and ethically problematic:

It devalues time, decisions, and relationships.

It can lead to moral apathy or egocentrism.

Mortality gives life depth, urgency, and responsibility.

That’s why many philosophical traditions agree: death is not the problem. Life without death is.

But what does that say about Dr. Manhattan? Is he missing what makes life worth living—or is he driven by duty alone?

CHAPTER 3: Becoming a Weapon

Dr. Manhattan is not merely a man accidentally transformed by science. He is science transformed into power, into myth, into a weapon. The United States government seized on his existence with calculated precision, turning him into a symbol of divine authority and nuclear dominance. His glowing blue figure became the face of victory in the Vietnam War. He ended the conflict in a matter of days. He’s the reason other nations hesitate to provoke conflict, the silent threat ensuring American hegemony.

Dr. Manhattan is a direct allusion to the American "Manhattan Project" of the 1940s—the development and construction of the atomic bomb. Notable: the symbol of hydrogen burned into his forehead in 1960 with a flick of his own finger. The U.S. government gave him the code name "Dr. Manhattan" to evoke fear among America’s enemies through nuclear association.

When the phrase “He’s American” is uttered, it’s not a statement of nationality—it’s a declaration of ownership. In this context, Dr. Manhattan is not a citizen; he’s property. A glowing embodiment of ultimate power under U.S. control. The omission of the article “an” strips him of personhood and subtly reinforces the notion that he no longer belongs in the realm of individuals with rights and identity. If Jon Osterman—the scientist, the man—were still seen as human, the phrase would be: “He’s an American.” That tiny grammatical distinction marks the difference between belonging to a nation and being claimed by it. It shows how language dehumanizes him, transforming him from a person into policy.

"I never said, 'The superman exists and he’s American.' What I said was 'God exists and he’s American.' If that statement starts to chill you after a couple of moments’ consideration, then don’t be alarmed. A feeling of intense and crushing religious terror at the concept indicates only that you are still sane."

— Wally Weaver

In Watchmen, this line encapsulates how the U.S. treats godlike power as an extension of its identity. And this isn’t an exception in American history—it’s part of a larger pattern: the tendency to frame violence in moral language and to rebrand war as righteous cause. From the Manhattan Project to the Cold War, the U.S. has continuously reinterpreted scientific discovery as a path to peace—through dominance. Tragically, this isn’t just political. It’s human. The impulse to use power "for good," to justify weapons as tools for stability, is both toxic and seductively rational. At least for some. It draws even the reluctant into its orbit.

Dr. Manhattan is not immune. Trained as a scientist, shaped by a post-Hiroshima worldview, he succumbs to the same narrative. Even if the world no longer sees him as human, the question remains: does he still hold onto a core of humanity—responsibility? The classic superhero idea that “with great power comes great responsibility” lingers in the background. Dr. Manhattan has the power to change the world, prevent suffering, act. And yet, he often chooses not to. That raises a painful question: If a godlike being watches tragedy unfold and does nothing, is he neutral, or complicit? At what point does inaction become silent endorsement?

That’s the real tragic. Dr. Manhattan isn’t just a symbol of American power. He’s a mirror held up to the moral burden that comes with it. And unlike Spider-Man, who is haunted by the cost of not acting, Manhattan seems to drift further and further from that sense of duty—until it might be too late.

CHAPTER 4: Purpose of Life

In Neil Gaiman’s graphic novels The Sandman, we meet an intriguing character who is granted eternal life through a wager. His name is Hob Gadling. Hob is a simple English soldier in the 14th century who, in a tavern, claims that he never wants to die—because he believes death is merely a habit, not a necessity.

The Dream King, Morpheus (Dream), hears this and proposes an experiment: he grants Hob immortality under the condition that they meet every 100 years in that same tavern to talk about life. Hob endures every conceivable hardship. He experiences hunger without starving, cold without freezing, and the pain of losing all those he loves, whom he outlives. Later, Hob becomes a brutal mercenary and trader. And yet, every 100 years, when he meets Dream again, he chooses life once more.

Their regular meetings evolve from an experiment into a real friendship. And in that friendship lies meaning—perhaps even more than in a goal. Hob was even involved in the slave trade at one point. Over time, he recognizes the injustice of his actions, repents, changes, and eventually becomes a compassionate and reflective person. In the end, it is Hob who teaches Morpheus what it means to value humanity.

Hob Gadling is one of the few fictional characters in which immortality is portrayed as realistic and fulfilling—not because it is easy, but because he grows, loves, suffers, and never stops being human. He embodies the answer to the question of life’s purpose:

Eternal life can be meaningful—if one is willing to change, take responsibility, and connect with others.

This kind of meaning only becomes clear to Dr. Manhattan much later, through a different truth he discovers. The unity of opposites.

And yet there’s also a striking parallel between Dr. Manhattan and Zima from Love, Death & Robots’ episode “Zima Blue” (S1 E14). Zima and Dr. Manhattan are both characters who undergo a deeply philosophical journey: from man to superman—and back. Their stories reveal that ultimate understanding is not found in omniscience or omnipotence, but in the simple, often overlooked act of being human.

Both characters experience, in their own way, the tragedy of transcendence. Dr. Manhattan can manipulate every atom in the universe. He sees past and future simultaneously. But the more he understands, the less he feels. Emotions fade in the face of eternal recurrence. People become predictable, interchangeable. Zima, too, reaches near-godlike status. His art becomes interstellar monuments. His insights span space and time—but none of it brings him fulfillment.

The turning point for both comes when they return to something small, seemingly insignificant. Zima, who once painted the cosmos, realizes his true identity was that of a simple cleaning robot. A being that scrubbed blue tiles, day after day. That repetitive, functional task was his origin and his peace.

Both stories teach us: those who search for meaning won’t find it in the infinite, but in the finite. In a touch, a decision, a glance. The divine seduces through control—but it’s our limitations that give life meaning. So their return to simplicity is not a step back, but a homecoming. And what pulls Dr. Manhattan back, if only briefly, isn’t logic or power—but love. The complexity of the cosmos suddenly fades in the face of genuine connection. Like Arwen choosing mortal life with Aragorn over a journey to the immortal lands of Valinor. A single, unlikely relationship with purpose. A "thermodynamic miracle."

CHAPTER 5: The Thermodynamic Miracle

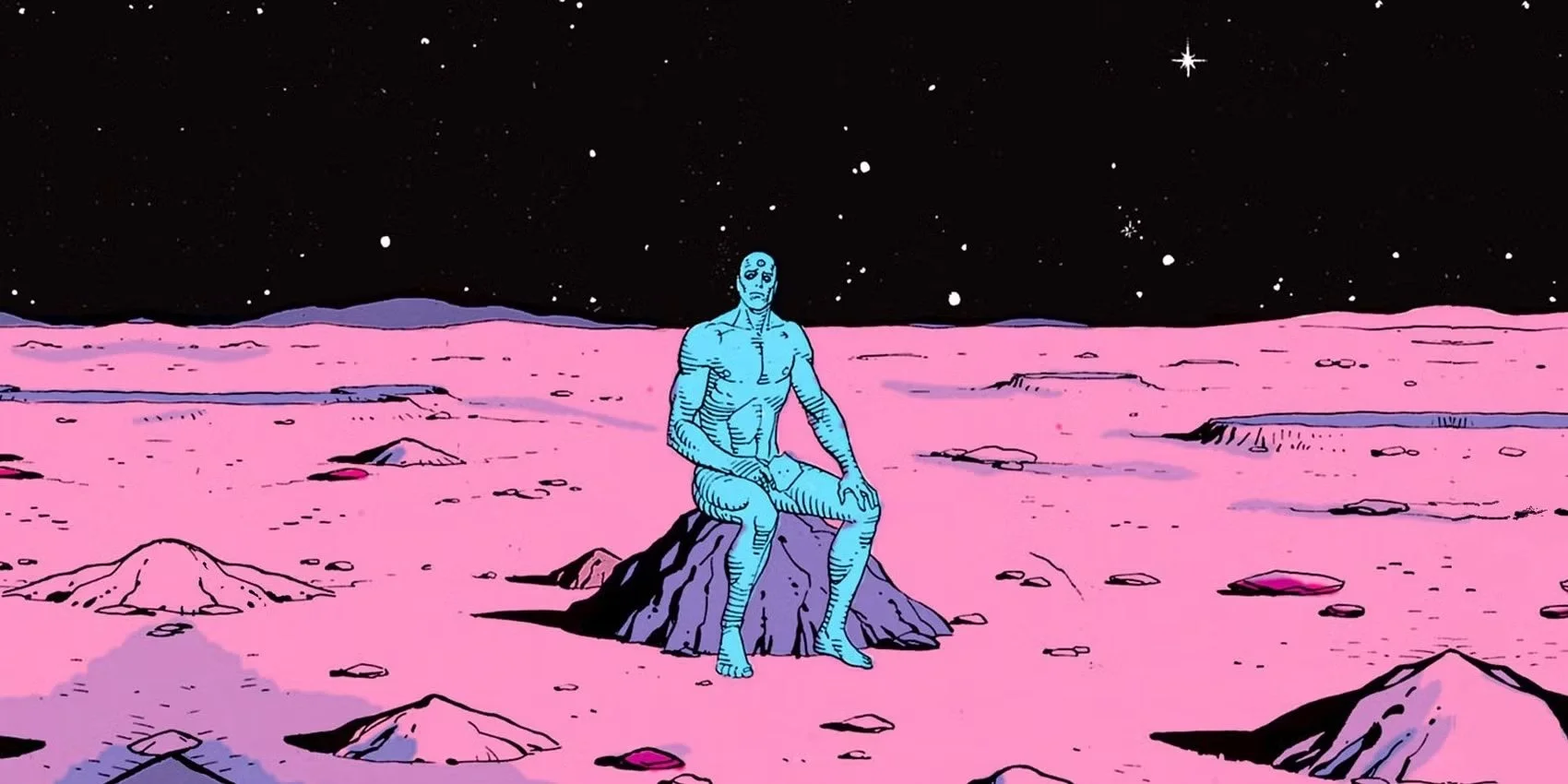

Dr. Manhattan’s relationship with Laurie Juspeczyk (Silk Spectre) serves as the last fragile thread connecting him to humanity. At a point when he has all but abandoned Earth, retreating to the sterile stillness of Mars, it is Laurie who pulls him back—not with logic or morality, but with a simple emotional truth. In one of Watchmen’s most poignant moments, Laurie’s realization of her improbable ancestry—being the product of a reluctant union between her mother and the Comedian—unlocks something in Jon. He calls it a “thermodynamic miracle”: the statistically impossible convergence of circumstances that led to her very existence.

For a being who perceives time as fixed and causality as deterministic, this spontaneous beauty in chaos reignites his appreciation for human life. It reminds him that even in a universe ruled by laws, meaning can still emerge—not despite entropy, but because of it. By recognizing Laurie as a miracle, Dr. Manhattan rediscovers his own capacity for wonder, and with it, a glimpse of the man he once was.

This is captured beautifully in their dialogue on Mars, adapted by Alex Tse:

But this realization would only be a single cog in the clockwork that would ultimately mark the end of his humanity.

CHAPTER 6: The Dilemma

At the end of Watchmen, after Adrian Veidt (Ozymandias) successfully executes his apocalyptic plan—sacrificing millions in a staged alien invasion to prevent nuclear war—Dr. Manhattan faces a moral dilemma. He realizes Veidt’s plan has worked. Humanity, gripped by fear of a common enemy, has united. The threat of global annihilation has been averted. But at what cost? Peace built on a lie?

In Zack Snyder’s 2009 film adaptation, the ending is altered: Veidt doesn’t fake an alien attack, but a global catastrophe caused by Dr. Manhattan himself.

Laurie and Dan (Nite Owl) are horrified. Rorschach wants to reveal the truth. But Dr. Manhattan, the only one with the power to stop Veidt, chooses not to. He kills Rorschach to preserve the fragile new balance. In doing so, Jon Osterman definitively abandons the moral compass of humanity. For him, the good of the many justifies the sacrifice of the few. A purely utilitarian mindset that underscores how detached he has become. Once again, emotion yields to logic. And yet, there is still a sliver of feeling:

"On Mars you taught me the value of life. If we hope to preserve it here, we must remain silent."

- Dr. Manhattan

Veidt is the villain who sacrifices millions to save billions. But Dr. Manhattan not only witnesses it. He chooses to let it happen. In Vietnam, he ended war by intervening. Here, he brings peace through inaction. Lives were lost either way. The uncomfortable truth: to preserve humanity, this outcome was the lesser evil. Peace through unity instead of domination. The price: his own humanity.

This leads him to his final decision. He realizes he no longer belongs on Earth. He is too powerful, too detached, too alien. Humanity doesn’t need him anymore and maybe he doesn’t need it either. Yet in this decision lies a hint of hope. The hope of finding meaning beyond humanity. In creation, in a new beginning, in his own thermodynamic miracles.

CHAPTER 7: The Clockwork God

Dr. Manhattan is more than a superhero. He is a living allegory for God, or at least for a very specific idea of God. To understand him fully, we need to go back 2,300 years to a man named Epicurus. Epicurus was the first philosopher to articulate what we now call the problem of evil, a challenge to the existence of an all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-good deity. His argument was simple and devastating. If God knows about evil, can prevent it, and wants to stop it, then why does evil exist? Either he does not know about evil, which would mean he is not all-knowing. Or he cannot stop it, which would mean he is not all-powerful. Or he chooses not to, which would mean he is not all-good. This dilemma has shaped theological debate for centuries.

During the Enlightenment, a new answer emerged through the Watchmaker Analogy. Thinkers like René Descartes and Isaac Newton proposed that God created the universe like a clockmaker. He built the mechanism, wound it up, and then stepped away. According to this view, God is not absent out of malice, but by design. He does not interfere because the machine runs on its own.

This concept fits Dr. Manhattan perfectly. His background as a watchmaker is no coincidence. After his transformation, he stops acting like a person and starts behaving like a detached observer. He no longer interferes in the affairs of humans. Instead, he watches as time unfolds from one cause to the next, just like a clock. The symbolism is clear. Dr. Manhattan becomes not just a god, but a god who chooses not to act.

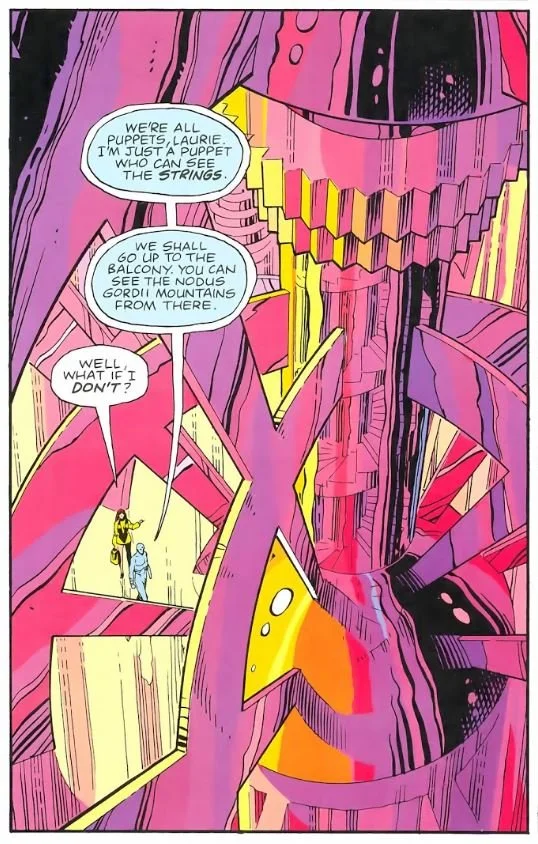

Why? One possible answer lies with Pierre-Simon de Laplace, a 19th-century philosopher who believed in determinism. According to Laplace, free will is an illusion. If someone could know the precise position and motion of every atom in the universe at a single moment, then the future would be as predictable as the past. Everything is determined. Nothing is uncertain. We are all just puppets, but only Dr. Manhattan is able to see the strings.

This theoretical intelligence is called Laplace’s Demon. But calling it Dr. Manhattan would work just as well. On Mars, we see that he experiences the universe much like Laplace’s Demon. He knows the future, not because he predicts it, but because he perceives it all at once. He sees all outcomes. And because he knows what he will do, he does it. Not out of choice, but because that action is already part of the chain of events. He does not intervene because he believes he cannot. He is no longer a moral actor, but a cog in the system.

We saw the consequences of this on a very human scale in Vietnam. When Edward Blake, the Comedian, murders a pregnant woman in cold blood, Dr. Manhattan is standing right there. He could have stopped it. He could have turned the bullets into steam or the gun into snowflakes. But he does nothing. Blake mocks him for it. In that moment, we see the horrifying result of a god who believes that all things are predetermined. He does not act because he believes he already knows what he will or will not do. Evil is allowed to happen, not because he is evil, but because he has surrendered the idea of responsibility.

By merging the imagery of the clockmaker god with Laplace’s Demon, Alan Moore gives us a terrifying picture of existence. In this vision, even a god is just another gear in the great machine of time. Dr. Manhattan might have once set the universe ticking. But now, like the rest of us, he simply listens to it tick.

CONCLUSION

Dr. Manhattan shows us that power without connection is meaningless. Immortality, omniscience, and invincibility isolate him—not because he is evil, but because he stops seeing himself as part of humanity. His story reminds us: it is not our powers but our relationships, our vulnerability, and our ability to find meaning in randomness that define us.

In the end, Dr. Manhattan is remembered not as a hero or a villain but as a quiet reminder that power requires responsibility, and even a god without love is just another machine in the cosmos.