THE HAMMER

A CINEMATIC OBSESSION

From gods and revolutionaries to vengeful anti-heroes —let's explore how the hammer became one of cinema’s most charged weapons.

Reading Time Estimated: 10 Minutes

Imagine: you’re watching Oldboy for the first time. Not the Spike Lee version — the real one. As the story unfolds you come to the hallway scene. One man, one hammer, and a corridor full of poor bastards who picked the wrong day. It’s brutal, it’s raw and it’s oddly beautiful. There’s no cutting away, no dramatic music. Just a hammer, gravity, and human bodies being reduced to meat and cracked bones. A rare phenomenon of violent aesthetic in cinema history.

It’s not the first time a hammer made its mark on cinema. Nor the last. In fact, hammers are everywhere — not just this Korean revenge thriller. From mythological weapons in billion-dollar blockbusters to grotesque tools of violence in arthouse horror, the hammer seems to pop up over and over again. It's not elegant and sharp like a katana, not distant and quick like a silenced gun. It's something else entirely. Something ancient, intimate, and dangerously improvised.

The hammer, as it turns out, is one of cinema’s most evocative story devices — part symbol, part threat, part psychological depth charge. It carries with it a primal weight: it's the tool of creation and destruction, of labor and punishment. When a character picks up a hammer in a film, it rarely ends peacefully. And yet, there's always a weird sense of logic behind it. It's not just about what it can do — it's about what it means.

So the question is: why the hammer? Why does it work so damn well in film? What is it about this blunt, inelegant object that makes it more than just a weapon? What does it tell us about violence, class, power — or maybe just about ourselves?

Let’s dive in:

1. A weapon of choice OR destiny?

Before it ever smashed a skull on screen, the hammer had already left its mark in myth, ritual, and real-world labor. Long before Oldboy or Marvel’s Thor, it was a symbol — one that belonged to gods, craftsmen, judges and revolutionaries. And like all good symbols, it was heavy with meaning.

Mjölnir and the Worth of Power:

Let’s start with the obvious choice when some speak about the hammer: Thor, son of Odin, wielder of Mjölnir. A god with flowing blond hair (or red, depending on the version) and a hammer that can channeling lightning, return to his hand, and crush mountains. In Norse mythology, Mjölnir is more than a weapon — it’s an emblem of divine authority. It blesses marriages, protects the cosmos from chaos and … oh yes, obliterates enemies with the sound of rolling thunder.

This isn’t just fantasy. Mythological weapons like Mjölnir often reflect real cultural ideals — strength, honor, protection of the tribe. The hammer becomes an extension of the self, a sacred tool. It’s not elegant, not refined — but it’s unstoppable. And that makes it cinematic gold.

The Gods Blacksmith:

Switch pantheons. Over in ancient Greece, we find Hephaestus, the god of fire, blacksmithing, and — fittingly — the hammer. Lame of leg, but sharp of mind, Hephaestus was responsible for crafting the weapons of Olympus. His forge birthed Achilles’ armor, Hermes’ winged sandals, and even Pandora — the first woman, created from clay and divine breath.

Hephaestus doesn’t wield the hammer to destroy, but to create. He’s the original maker, the mythic artisan. His hammer symbolizes skill, craftsmanship, and transformation. It's a quieter kind of power, but no less profound. And when film taps into this — say, in a montage of someone forging their weapon or an armor like Tony Stark — it’s Hephaestus spirit whispering with every strike.

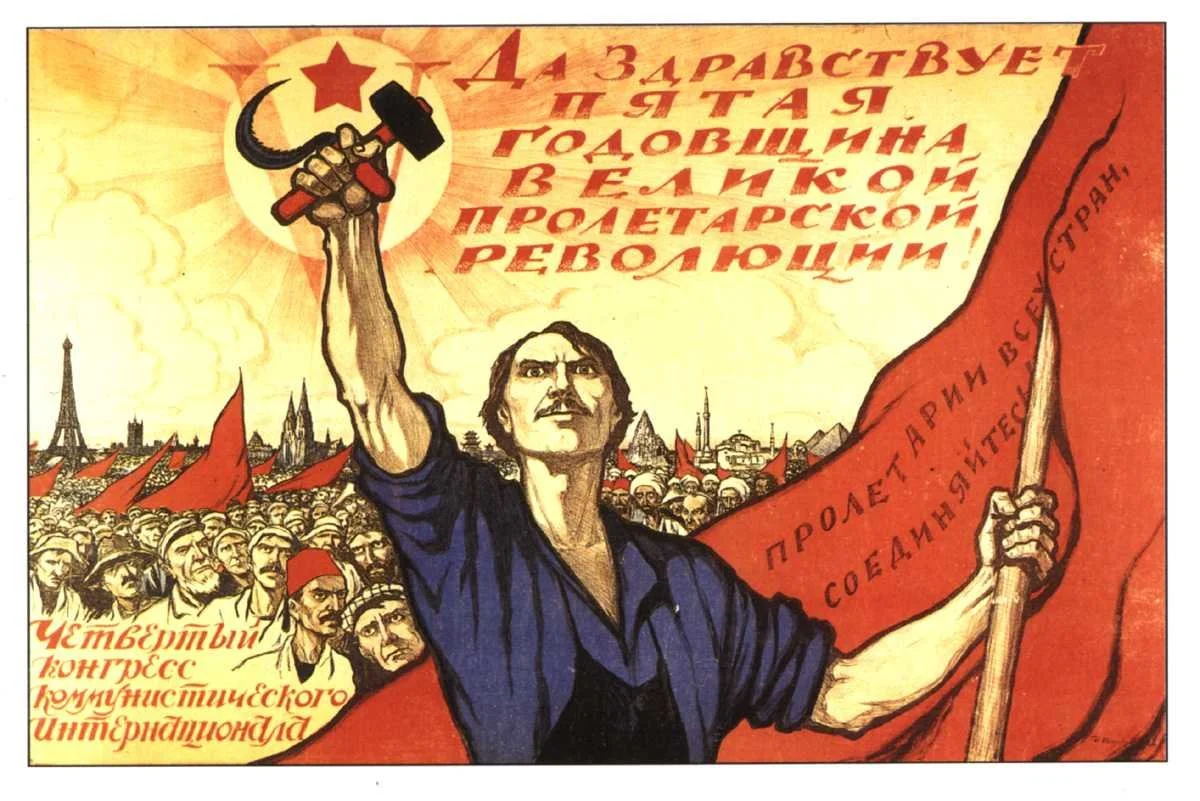

Hammer-Revolution:

Fast-forward to 1917. The hammer gains a new kind of iconography — this time political. Paired with a sickle, it becomes the emblem of the working class in Soviet Russia. No longer divine, the hammer stands for laborers, the everyday person, the masses. It's no longer a weapon of the gods, but of the people. And that shift is crucial.

When filmmakers put a hammer into the hands of a character today — especially someone on the margins, someone with no formal training or access to traditional weapons — there’s often a quiet nod to this idea. It’s a tool, not a gun. A worker’s object. You find it in your garage, not your armory. And that makes it inherently relatable, even when it’s used in acts of extreme violence.

It could be a pastry roller or a pan as well but let’s admit that a hammer is much cooler as a symbol.

A Symbol for Law:

Even outside the battlefield or crime scene, the hammer holds symbolic power. In courtrooms around the world, judges wield a gavel — a small hammer — to command order, deliver judgments, and ultimately enforce the authority of law. The gavel symbolizes finality and control, embodying the power to shape lives with a single strike. It reminds us that every decision, every act of judgment, carries the weight of creation and destruction — a verdict can build a future or shatter it.

First Tool of Mankind:

There’s something deeply human about the hammer. It's been with us since the Stone Age — literally. The first tools we made were percussive, designed to crush, to shape, to build. Our entire civilization is hammered into existence. So when we see a hammer on screen, it doesn’t just read as a weapon. It reads as history. As work. As intent.

And unlike a sword or a firearm, a hammer requires proximity. You have to get close. You have to feel the impact. That’s what makes it so visceral — and so cinematic.

So when the hammer shows up in films — whether it’s gripped by a vengeful father, a god of thunder, or a desperate woman defending herself — it brings with it a lineage that spans myth, labor, violence, and transformation.

And that’s just the beginning.

2. A Weaponized Tool in Genre Film

There’s something uniquely terrifying about a hammer in a fight. It’s not sleek like a knife, not impersonal like a gun. It’s raw. Heavy. Brutal. It doesn’t cut — it crushes. And that physicality, that blunt honesty, makes the hammer a recurring guest in some of cinema’s most violent, most memorable moments. The hammer doesn’t ask for permission. It doesn’t negotiate. A few examples:

Horror:

In horror films, the hammer isn’t just a weapon — it’s a declaration of intimacy. Think Misery (1990), where Annie Wilkes (Kathy Bates) doesn't just kill — she hobbles. With a sledgehammer and a block of wood. It’s one of the most disturbing scenes in horror history, precisely because of how close it feels. You hear the crunch. You feel it in your bones.

Or take The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), where the hammer isn't neat or choreographed. It’s ugly, animalistic. The thud of metal on skull is filmed with documentary-like coldness. No slow motion, no glamour — just the sickening sound of reality. The message? This isn’t heroism. This is slaughter.

Horror uses the hammer not just to kill — but to unnerve. It reminds us that violence isn't always theatrical. Sometimes it’s just... loud.

The Hammer equals death

Thriller & Action:

Jump to Oldboy (2003), and we’re in a whole different aesthetic. The now-iconic hallway scene is choreographed like a dance — messy, yes, but beautiful in its chaos. One man, a claw hammer, and a dozen thugs in a narrow corridor. No cuts. Just determination and impact. It’s not about winning. It’s about endurance.

Here, the hammer becomes a symbol of stubbornness. Of justice twisted into vengeance. Dae-su’s weapon isn’t special. It’s not chosen by destiny. It’s just… what was there. And that’s what makes it powerful. It’s not a superhero’s tool — it’s a desperate man’s.

Then there’s Drive (2011), where Refn turns the hammer into a quiet threat. Ryan Gosling’s Driver doesn’t explode — he simmers. In one unforgettable scene, he corners a man in a strip club, gently presses a bullet on his forehead, ready to strike it with the hammer, and delivers an ultimatum. The violence is minimal. The tension? Off the charts. Here, the hammer is not just a weapon — it’s a promise.

The Hammer equals vengeance

Superheroes:

Of course, no cinematic hammer talk is complete without Mjölnir. In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Thor’s hammer is less a tool and more a personality test. “Whosoever holds this hammer, if they be worthy, shall possess the power of Thor.”

It’s not just about who can use the hammer — it’s about who should. Worthiness becomes narrative fuel. When Captain America nudges it in Age of Ultron, the crowd goes wild. When he finally wields it in Endgame, it’s not just fan service — it’s a well earned payoff to years of character-building.

In this context, the hammer represents moral clarity. Power that comes not from rage, but from righteousness. But even here, it’s still a weapon. One that levels cities and gods alike.

The Hammer equals justice

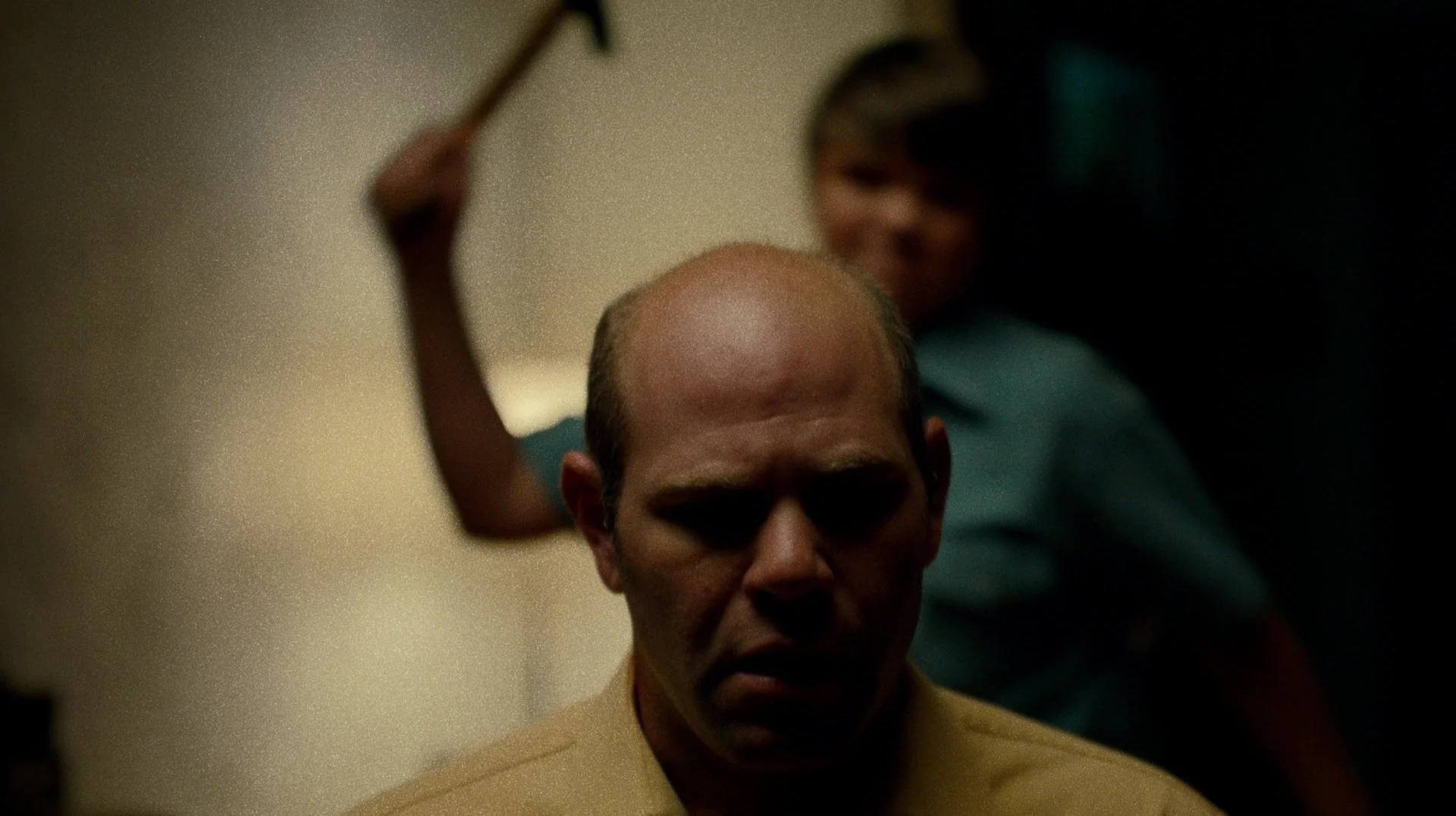

Where heroes rise, villains are sure to follow. In Netflix’s Daredevil, the hammer once again becomes a brutal tool of transformation. As a young boy, Wilson Fisk — the man who would become the Kingpin — murders his abusive father with a hammer after years of violence and humiliation.

Driven by fear, desperation, and a sudden, uncontrollable surge of rage, Fisk’s act is not one of heroism, but of survival and fractured identity. The hammer, meant to build and create, becomes the weapon through which Fisk severs himself from his past — but in doing so, he lays the first stone on the dark path toward becoming a monster himself. In Daredevil, the hammer is not just a murder weapon. It is a grim catalyst for the birth of a villain.

The Hammer equals a twisted form of justice

Western:

In Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012), during the brutal mandingo fight scene, Calvin Candie casually tosses a hammer to one of the combatants.

On the surface, it is merely a weapon — a tool to finish the fight. But on a deeper level, the hammer becomes a symbol of finality: the last nail driven into the coffin of the loser's life, while simultaneously fortifying the survival of the victor.

It reflects the dual nature of the hammer once more: an object that both destroys and builds, that ends one life while enabling another to continue.

Through this simple gesture, Tarantino taps into the primal symbolism of the hammer — survival carved out by force, and existence bought through violence.

The Hammer equals a trade

What makes it special:

Unlike guns or swords, hammers weren’t designed for violence. That’s what gives them their tension. They’re borrowed. Repurposed. Improvised.

That’s why the hammer works so well across genres. It adapts. In horror, it horrifies. In thrillers, it empowers. In superhero films, it sanctifies. The same object — different meanings, different worlds.

But one thing always stays the same: you feel it.

Hammer vs. Axe - A quick Excursion:

At first glance, a hammer and an axe might seem like cousins — both tools turned weapons, both blunt enough to feel raw, but precise enough to inflict serious damage. And yet, when they appear on screen, they tell very different stories.

The Axe: Sharp, Wild, Slaughter

Where the hammer crushes, the axe cuts. Its very design demands momentum, cleaving, severing. It's about splitting something apart — wood, bone, people. And because of that, the axe carries a different emotional resonance: it feels wild. Unstable. Messier.

Take the movie Hatchet (2006) or the infamous axe murder scene in Dread (2009), directed by Anthony DiBlasi. There’s no clinical execution here, no methodical bludgeoning. It’s chaos. Fear. Screaming. The axe doesn’t just kill; it dismembers. It tears reality apart, visually and emotionally. Watching an axe on screen is almost always more horrifying than watching a hammer — because axes imply a total loss of control. They’re less about punishment and more about annihilation.

Thor’s Evolution

Even Thor, the God of Thunder, had to upgrade. After the destruction of Mjölnir, he forges Stormbreaker — a hybrid weapon that’s part hammer, part axe. But symbolically, it’s a big shift.

Mjölnir was about worthiness. It was clean, absolute, almost ritualistic in its power. Stormbreaker, on the other hand, is brutal. It’s bigger. Hungrier. Its axe blade suggests aggression, offense, and destruction on a grander scale. And fittingly, Thor’s character at that point (Infinity War) is darker, more desperate. Stormbreaker isn’t about judgment — it’s about survival and revenge.

In other words: Mjölnir judged. Stormbreaker slaughters.

Two spirits of cinematic violence

In film, hammers tend to represent intentional violence. There's weight behind every blow. There's struggle, yes — but also a strange intimacy. Axes, by contrast, often symbolize out-of-control violence. They suggest the body acting faster than the mind, blood before thought.

Both tools-turned-weapons are deeply cinematic. But the emotions they tap into? Worlds apart. The audience subconsciously reads these nuances.

In both cases, it’s not just external violence. It’s internal collapse. It reflects the thin line between civilization and chaos — the idea that beneath our polished surfaces, violence is never far away. And that’s why these weapons haunt us longer than a thousand faceless gunfights.

They become emotional detonators.

3. Cinematic Expression

You don't just see a hammer on screen. You hear it. You feel it.

The physicality of the hammer demands a different kind of filmmaking — one that emphasizes weight, resistance, and brutal finality. Directors know this. And when they choose to feature a hammer as a weapon, they often adapt the entire language of the scene around it. It’s not about the number of hits. It’s about the meaning behind each one.

Camera: Close encounter

A hammer fight is intimate. That’s why the camera often moves in close. Tight framing. Handheld shots. No wide, glamorous views.In Oldboy, the legendary hallway scene traps the audience in the same claustrophobic corridor as Dae-su. We don’t get the luxury of distance. Every swing feels like it might hit us. Close-ups of sweaty faces, trembling hands, the slow tightening of a grip — these are the trademarks of hammer scenes. Combined with the wide parallel view to the corridor makes it both daringly close yet artistically beautiful to watch on a wide screen.

Sound Design: The Sound of violence

A hammer doesn’t slice through the air like a sword. It doesn’t crack like a gunshot. It thuds.

A wet, heavy, unforgiving sound. Directors often highlight this acoustically — exaggerated impacts, muted environmental noise, hyper-focused soundscapes.

In You Were Never Really Here, Lynne Ramsay uses sound not to glorify violence, but to reveal its horror.

Each hammer strike is less a triumphant blow and more a hollow, pathetic echo of trauma. It doesn’t sound victorious. It sounds sad.

Good hammer scenes make the audience flinch not because of what they see — but because of what they hear.

Movement:

Sometimes, filmmakers choose to stylize hammer scenes.

Slow motion — like in Drive — turns a hammer into a symbol of inevitability. You know the blow is coming. You see it unfold in agonizing detail. Or take the repetitive structure of Dae-su's hallway battle: hit after hit after hit. It’s not elegant. It’s exhausting. And that exhaustion bleeds into the audience.

Good hammer scenes don’t just show a fight. They drag you through it.

Aestetic:

Ultimately, hammer violence on screen is a deliberate choice.

It refuses the sleekness of guns, the nobility of swords, the flashy spectacle of explosions.

It’s ugly. Personal. Real.

And because of that, it can be beautiful — in the way tragedy can be beautiful.

Not because we admire the act itself, but because we recognize something raw and terrifying in it. Something human.

And maybe that's why, when the credits roll and the lights come back on, it's not the clean gunshots or fiery explosions we remember.

It's the quiet, heavy weight of a hammer — and everything it says without speaking a word.

Because sometimes, the loudest screams are made of steel and silence.

4. A vessel FOR emotions

In cinema, the hammer is more than just a tool of destruction — it is a vessel for inherited pain, psychological trauma, and existential rebellion. This essay explores how filmmakers use the hammer to shape complex characters, expose inner violence, and elevate raw brutality into a language of emotion and meaning.

A hammer kill is often slow, heavy, messy. It suggests proximity — the attacker has to be close, has to feel the resistance of flesh, bone, and spirit. A strike not just hits his opponent but shakes his own body as well. There's no clean distance like with a sniper rifle or an explosion. You have to get your hands dirty. You have to choose it. You even have to make eye contact and see how live fades.

That intimacy is what triggers something primal in the viewer: Empathy mixed with horror.

The brain almost mirrors the act. We wince. We recoil. Our body reacts because the violence is uncomfortably personal. Sometimes, a hammer isn’t just a weapon. It’s a memory. A regret. A burden.

In many films, the hammer is less about what the character does — and more about why they do it.

Take Joe in You Were Never Really Here: The hammer he wields against his enemies is the same kind of weapon his father used to abuse him as a child. Every swing, every broken bone is a physical manifestation of trauma — a desperate attempt to take back control over a past that left him broken.

Violence, here, is not victory. It’s mourning. The hammer becomes a symbol of a cycle that Joe can’t escape: hurt people hurting others. And Ramsay films it accordingly — muted colors, fragmented memories, a soundtrack that sounds more like drowning than triumph.

Joe doesn’t kill because he enjoys it. He kills because he doesn’t know how else to scream.

Thor's hammer, by contrast, is inherited power — but it too carries a psychological weight.

Worthiness. Responsibility. Expectation. When Thor loses Mjölnir and crafts Stormbreaker, it’s not just a weapon upgrade. It’s a collapse of identity. He’s no longer the golden prince of Asgard. He’s a broken man wielding a weapon of mass destruction. Stormbreaker doesn’t choose Thor. He chooses it — out of desperation, guilt, and grief.

The audience feels that shift intuitively. The hammer (or axe) becomes less about power and more about pain. About proving something — to others, to oneself, to the ghosts that refuse to leave.

Films know that a hammer tells a story without exposition. When a character lifts a hammer, we understand: this is personal. This isn’t strategy. This isn’t efficiency. It’s emotion turned physical.

5. A Cultural dance of the hammer

Not every hammer comes from the realm of gods. Some come from the dirty alleyways, the subway stations, the brutal heartbeat of survival.

In Gareth Evans’ The Raid 2 (2014), a character simply known as Hammer Girl brings the weapon into a new context: the fiercely physical, bone-crushing world of Southeast Asian martial arts cinema.

Armed with two claw hammers, she moves through her enemies with a fluidity that borders on dance — a ballet of broken bones and shattered skulls.

Her fighting style blends Indonesian silat techniques with pure improvisational brutality, creating a visual rhythm.

Unlike the mythic hammers of Western superhero films, Hammer Girl's weapons aren't symbols of destiny or lineage. They are just what they are: Tools.

Where Hollywood often polishes violence into spectacle, Southeast Asian action cinema embraces its rawness. Every swing, every impact in The Raid 2 feels heavy and real but with some kind of gracefulness. Hammer Girl's battles are fast, but never weightless — every hit carries the echo of broken ribs, the sickening crunch of realism. And yet, there’s undeniable beauty in the choreography.

Through Hammer Girl, the hammer becomes something new:

Not just a tool of vengeance. Not just a symbol of trauma. But a pure, kinetic expression of willpower against overwhelming odds.

While Western cinema often frames hammers through the lens of mythology or psychological trauma, films like The Raid 2 remind us that, in other cultures, the hammer can simply be what it always was.

Hammer Girl doesn't need a backstory of divine right or childhood trauma to justify her violence. Her story is written in movement, in impact, in survival. And perhaps that's the rawest, most honest form of storytelling there is. Nothing else needed.

CONCLUSION

The hammer joins a vast family of improvised weapons.

Whether it’s an axe, a chainsaw, or a baseball bat — What begins as utility is corrupted by the darkest corners of human imagination, touching the raw nerves of both character and audience alike. For as long as we have shaped the world with our hands, we have also shaped weapons from the very same tools. The hammer is no different. The hammer, saturated with emotion and significance, stands as a relic of that dual nature — a tool for creation, and a harbinger of destruction.

That is what cinema has observed throughout history. It did not invent the hammer as a weapon, but it understood the essence and nature of this object, holding up a mirror to us and reflecting the darker corners of our own humanity.

Films know that a hammer tells a story without exposition.

When a character lifts a hammer, we understand: this is personal.

This isn’t strategy. This isn’t efficiency. It’s emotion turned physical.